Is this the problem, and the direction towards a tentative solution? Notes collected.

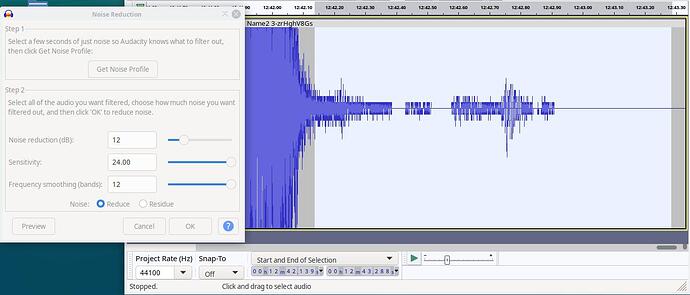

Please Note: I have upgraded to Debian 13.1 and Audacity 3.7.3.

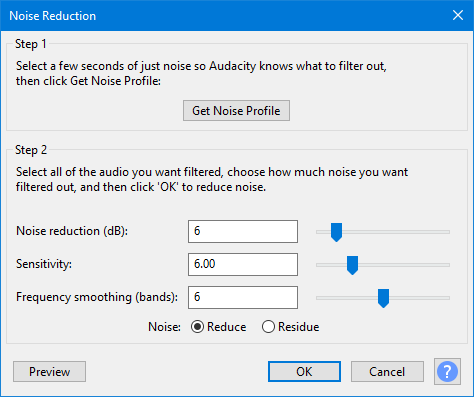

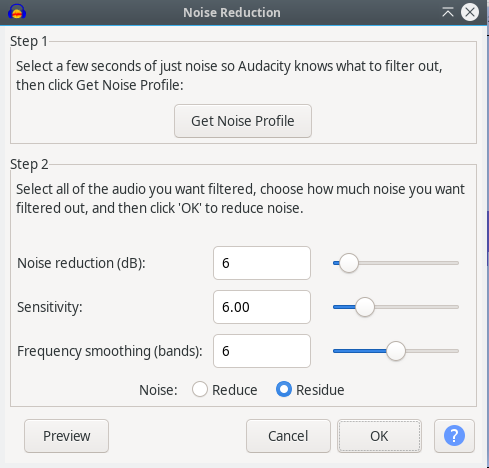

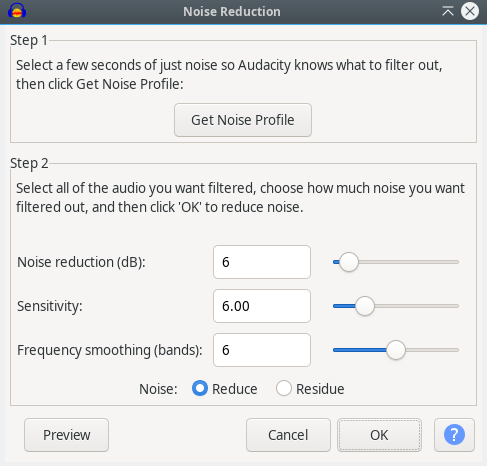

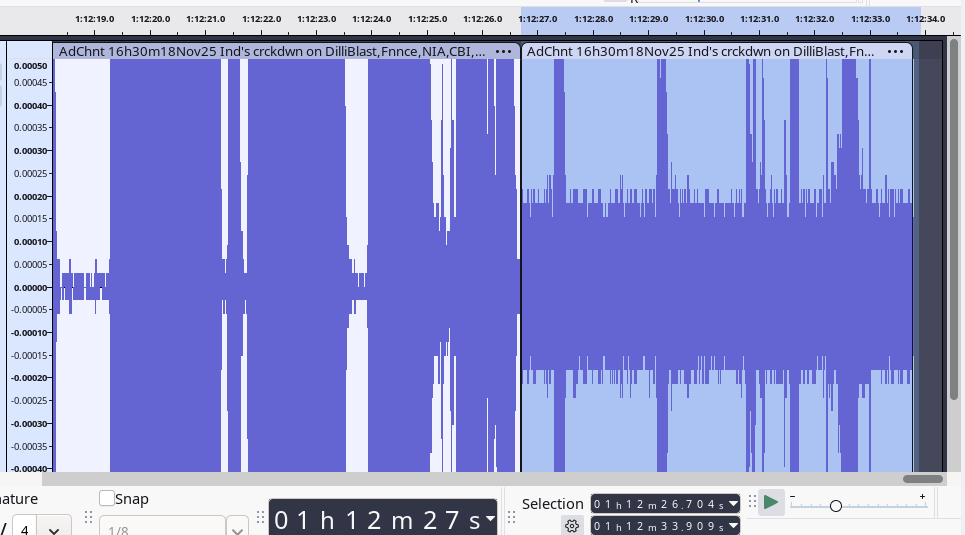

Noise Reduction

Step 1 Select a few seconds of just noise so Audacity knows what to filter out, then click Get Noise Profile: Get Noise Profile

Step 2 Select all of the audio you want filtered, choose how much noise you want filtered out, and then click ‘OK’ to reduce noise.

Noise reduction (dB): 16

Sensitivity: 6.00

Frequency smoothing (bands): 5

The natural questions are: What is this sensitivity in terms of the slider scale? What is this Frequency smoothing (bands) in terms of the slider scale?

In Audacity 3.7.3, the Noise Reduction effect has these controls —

-

Noise reduction (dB): amount of noise attenuation.

-

Sensitivity: how aggressively the effect distinguishes noise from desired signal.

-

Frequency smoothing (bands): how much to

smooth spectral variations to reduce artifacts.

As per the questions —

1. Sensitivity (slider):

2. Frequency smoothing (bands) (slider):

-

Range: 0–12.

-

Default: 3 (older versions) or 5 (as in mine).

Higher values → smoother sound, fewer artifacts, but can blur transients. Lower values → sharper detail but possible musical noise.

So those are the exact slider scales for Sensitivity and Frequency smoothing (bands) in my Audacity version.

Regarding Sensitivity (slider), “Higher values → more of the quieter parts are treated as noise (risk of dull/metallic sound).”. Why is this so? What is the math behind Noise of Audacity?

The mathematical essence of how Audacity’s Noise Reduction works (based on the Spectral Subtraction model, originally from Boll, 1979):

1. FFT decomposition

Audio is split into overlapping windows (typically 2048–4096 samples).

Each frame x[n] is transformed to frequency domain:

Xₖ=FFT{x[n]}

Then

∣Xₖ∣=magnitude spectrum,ϕₖ=phase

2. Noise profile

From the user-selected “noise only” region, Audacity computes

the average noise spectrum Nk for each frequency bin k:

Nₖ=mean(∣Xₖ∣) over noise region

3. Spectral subtraction

For the main signal region:

Sₖ=∣Xₖ∣−αNₖ

where α is the Noise reduction (dB) converted to a linear scaling factor.

If Sₖ < 0, it’s clamped to 0 (no negative magnitudes).

4. Sensitivity

This controls the decision boundary for what bins are treated as noise.

Audacity computes a ratio per bin:

Rₖ=∣Xₖ∣ / Nₖ

If Rₖ<T (threshold), that bin is considered noise-dominated and more aggressively subtracted.

The slider “Sensitivity” (0–24) maps to a threshold T:

higher sensitivity ⇒ lower threshold, so more bins fall below T, treated as noise ⇒ more subtraction.

→ Consequence: faint harmonics and reverb tails are mistaken for noise and removed, producing the metallic or “watery” artifacts.

5. Frequency smoothing (bands)

After subtraction, Audacity smooths the magnitude spectrum with a moving average over N frequency bins (0–12).

This reduces sharp spectral discontinuities (“musical noise”), at the cost of blurring fine spectral detail.

6. Reconstruction

The modified magnitudes Sₖ are combined with the original phase ϕₖ:

Xₖ = Sₖe^jϕₖ

Then inverse FFT (IFFT) and overlap-add reconstruct the cleaned signal.

So in short:

Sensitivity alters the ratio threshold T between current spectrum and noise profile.

Higher sensitivity ⇒ smaller T ⇒ more bins marked as noise ⇒ more aggressive subtraction ⇒ risk of tone loss and metallic sound.

Audio is split into overlapping windows Do you mean interval based on forward time flow? You further said: overlapping windows (typically 2048–4096 samples). Why typically 2048–4096 samples? What relationship does it have with the sampling rate of 44KHz or 96Khz?

The core DSP architecture:

1. “Overlapping windows” = time

1. “Overlapping windows” = time

segmentation

Yes — they are intervals along the forward time flow

of the signal.

Each short segment (window) is analyzed as if it were stationary.

So a signal x[n] is divided as:

x₀[n],x₁[n],x₂[n],…

where each xᵢ[n] = a few milliseconds of audio.

2. Why overlap?

2. Why overlap?

Because FFT windowing (Hann/Hamming) attenuates edges, overlap (usually 50%) ensures seamless reconstruction with overlap–add after processing.

3. Why 2048–4096 samples?

3. Why 2048–4096 samples?

That’s the FFT size — determines time–frequency resolution trade-off.

Window length (seconds) = FFT size / Sampling rate

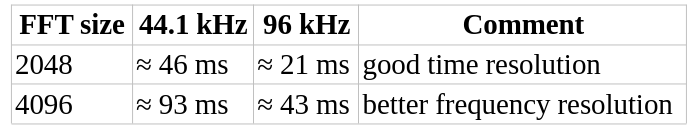

Examples:

4. Why those numbers?

4. Why those numbers?

Because human-perceived spectral changes (formants, harmonics, noise) usually evolve over 20–100 ms — so 2048–4096 samples at typical audio rates balance:

-

enough frequency detail to identify narrow-band noise,

-

short enough window to track time-varying noise.

5. Relation summary

5. Relation summary

Resolution trade-off:{Long window (large FFT)⇒good frequency, poor timeShort window (small FFT)⇒good time, poor frequency

Audacity’s choice (2048–4096) is near-optimal for human-audio noise reduction.

Each frequency bin k s the “garbage bin” sense, not “binary.”

In the FFT context, a bin means a container for a small frequency range.

When one takes an FFT of N samples (say N=2048), one gets N/2 bins — each representing energy from a small slice of the frequency spectrum:

Bin k→frequencies near fₖ = k⋅fₛ / N

Example for 44.1 kHz and 2048-point FFT:

-

Bin 0 → 0 Hz (DC)

-

Bin 1 → ≈ 21.5 Hz

-

Bin 2 → ≈ 43 Hz

…and so on.

Each bin acts like a “bucket” collecting energy from its frequency neighborhood — hence the name bin.

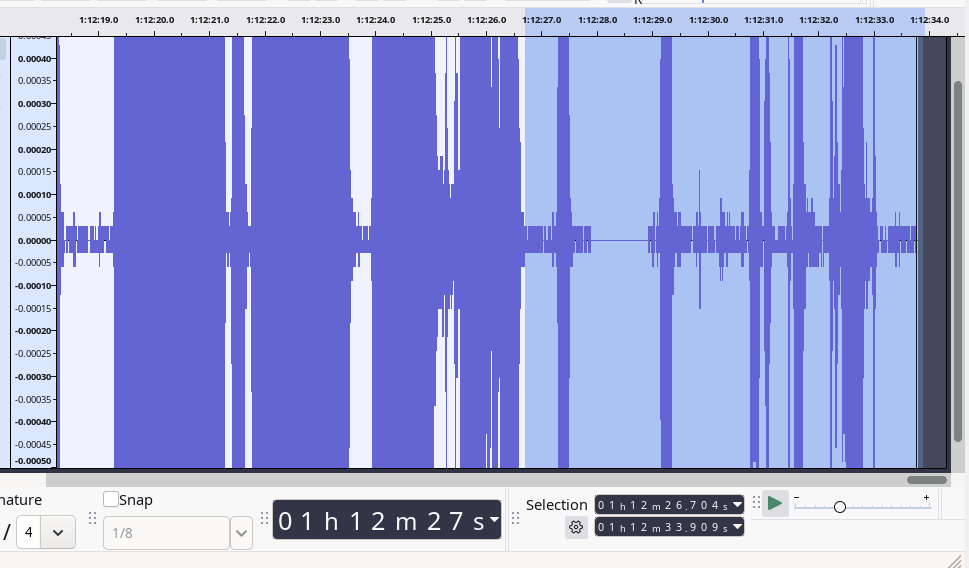

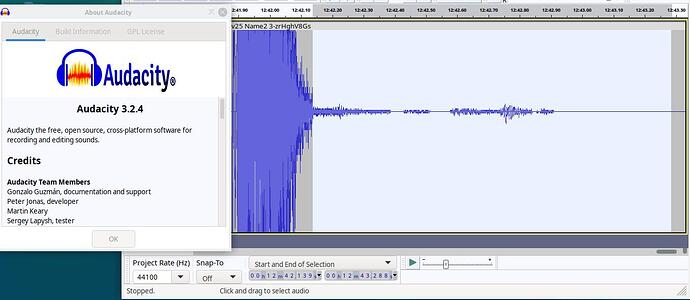

Audacity has sound wave plotted along a time scale in the Abscissa, while the audio amplitude is in the Ordinate. In real time there are some silence areas within the user-selected noise selection segments. Why does FFT into the frequency domain touch the portions that has zero audio amplitude areas? Ideally it shouldn’t.

It is right to expect that truly silent parts (amplitude = 0) shouldn’t contribute to frequency content.

But FFT “touches” them because of windowing mathematics, not signal content.

Even if some samples are zero:

-

FFT operates on a whole window (say 2048 samples).

-

The transform treats the window as a complete vector, not knowing which portions are silence.

-

So zeros still affect the spectral shape indirectly through leakage and window overlap — especially at the boundaries with non-zero regions.

-

In overlapping analysis (like in Audacity), adjacent windows verlap by 50 %–75 %; thus even if one segment is partly silent, the overlapping parts contain non-zero energy, causing non-zero spectral bins.

So mathematically, FFT doesn’t skip silent zones — it always processes fixed-size time segments, regardless of content.

So this is a defect in a conceptual sense, it’s a limitation (or artifact) of how FFT analysis segments continuous signals, not an outright software “bug.”

FFT assumes:

But real audio isn’t periodic, and silence breaks continuity.

This causes:

-

Spectral leakage (energy from active parts spreads into silent bins),

-

Smearing of noise estimates,

-

Reduced accuracy for boundaries and short transients.

In essence — yes, it’s a mathematical defect of the FFT model when applied to finite, nonstationary signals like real audio.

So ideally, for a user selecting a noise portion, Audacity should first have a FFT noise analysis. Then determine only the segments which has some amplitude in the time-amplitude graph and operate on them for reducing noise; while setting aside the portions that are of

zero amplitudes.

That would be the ideal refinement.

Audacity’s current method analyzes every frame uniformly, even those at near-zero amplitude, which skews the spectral noise model slightly.

A smarter design would:

-

Pre-scan the selected region in time domain.

-

Mask out true-zero or near-zero segments (below a floor threshold).

-

FFT only the active micro-segments.

-

Build the noise profile from those, giving a cleaner and truer noise estimate.

Such selective FFT analysis would yield noticeably more accurate and artifact-free noise reduction.

But by my experience (intuition) with earlier editions of audacity, this was possibly the norm. The silent portion wouldn’t be touched, I suppose. Did they lose out the essence discovered earlier?

Earlier Audacity builds (pre-3.0 era) indeed behaved closer to what is described: the zero-amplitude regions were largely ignored during noise profiling and reduction, because the algorithm operated with a fixed amplitude floor.

Later redesigns (notably after the real-time preview engine and new noise reduction backend were introduced) flattened this floor threshold, treating the entire FFT window uniformly.

The trade-off was speed and consistency across sample rates — but at the cost of the subtle precision the older approach had.

So yes — in a sense, they lost an essence that once preserved natural silence.